Fascinating wildlife facts: surprising secrets from your garden

As Sir David Attenborough says, “No one will protect what they don’t care about; and no one will care about what they have never experienced.” The more we learn about the wildlife and plants right outside our window, the more we appreciate and protect them. I’ve spent the past year researching facts that have transformed the way I view the everyday animals and plants in our garden. I wanted to share these insights with you in the hope that you find the information as fascinating as I do.

Squirrel memories

Squirrels have incredible memories. They can scatter-hoard several thousand nuts in a single season and then remember where most were hidden come winter. They will also feign the burying of nuts to misdirect potential competitors and keep their stores for themselves. Urban foxes use a similar strategy and can remember where they’ve hidden their food, but squirrels are clear winners in the memory game.

Scuba frogs

On the most part, frogs rely on their lungs to breathe just like we do, but they can also breathe through their skin – an adaptation called cutaneous breathing. They absorb oxygen and dispel carbon dioxide directly from their bloodstream, which allows them to survive for long periods underwater and in colder temperatures. The process relies on a frog’s skin being moist, which is why you’ll often find them in damp environments. It also makes them really sensitive to pollution, which makes them great bio-indicators – if you have frogs in your garden, it’s a sign that you have a healthy ecosystem.

Living bridges

Wood ants, common in British woodlands, work together to build huge nests woven with pine needles. When they encounter gaps in the terrain, they link their bodies together to create a living bridge for their teammates to cross, keeping food and supplies moving unhindered back to the nest. The red ant goes a step further and can create a raft using their bodies, which they use to protect the queen ant if their nest becomes waterlogged. The raft lasts for several days until the colony reaches dry land again.

Bluebell clues

Bluebells tell a story about the health and history of our woodlands. They’re considered an ancient woodland indicator species, which means that if you find them growing in large numbers, you’re probably standing in a woodland that has been there for at least 400 years. Some wildflowers spread quickly, but bluebells are very slow to establish, and their presence suggests undisturbed soil and stable conditions. British bluebells are protected – they are vital for early pollinators and a natural weed suppressant for the woodland floor, but they are threatened by tramping feet, deforestation, and imported Spanish bluebell varieties. Our native bluebells are a deep violet-blue with a sweet scent and flowers that droop slightly to one side, whereas the more invasive Spanish bluebells are paler, more upright, and less scented.

Magnolia traps

Magnolias have been on Earth far longer than we have, and the common pollinators we see today hadn’t even evolved when the trees first bloomed. They were pollinated by early, flightless beetle species (trees pollinated by beetles usually have pink or white flowers) and evolved tough flowers to withstand the beetles chewing. At night, a magnolia will close its flowers, trapping any lingering beetles inside, before opening up to send them on their way to the next plant in the morning, all covered in pollen.

Hedgehogs can swim

Hedgehogs aren’t built for aquatic life, but they have been known to swim short distances across rivers and ponds to find new territories or search for food. They can even float on their backs when they’re tired, thanks to air-filled sacs on their spines! Despite their swimming skills, hedgehogs find it nearly impossible to climb out of steep-sided ponds, which is why it’s so important to make sure your pond has a shallow access ramp that will allow them to escape when they need to.

Intelligent blackbirds

Songbirds are able to sing because they have specialised vocal organs and brains that allow them to recognise, learn, and recall songs. Blackbirds have a particularly beautiful, fluting song, which I think sounds like it’s in a major key. Like some other birds, blackbirds can mimic sounds they hear in the environment around them, and they are also clever enough to recognise us. Feed a blackbird regularly, and he will learn to approach you confidently. But if you disturb his nest, a blackbird will remember your face and rise up with an alarm call in the future.

Freezing frogs

Our garden frogs can withstand truly cold temperatures. To do so, they freeze parts of their bodies and then thaw as winter passes. The wood frog in North America goes further – they can freeze their entire bodies solid, effectively putting their metabolisms on hold. These amazing animals produce a substance that acts like antifreeze and can thaw themselves out when spring comes around.

Ladybird spots

When we think of ladybirds, we often imagine the familiar seven-spot red and black insects. However, we have over 40 different species of ladybird in the UK – some are cream, some are black with red spots, some are yellow, and the lichen ladybird is brown. Some ladybirds even have no spots at all! You can tell the age of a seven-spot ladybird by its markings, which fade over time.

How does a woodpecker peck?

Woodpeckers drum thousands of times each day, especially at this time of year. I had always read that they protect their brains with shock-absorbing layers of tissue inside their skulls, but recent research has debunked this theory. It seems that woodpeckers have incredibly dense and rigid skulls, which transfer energy away from the brain as they tap. Their beaks work like chisels, transferring energy into whatever they’re tapping, and their brains are small and tightly packed, which helps minimise impact. This discovery has changed the way scientists think about biomechanics and has potential applications for technology and engineering.

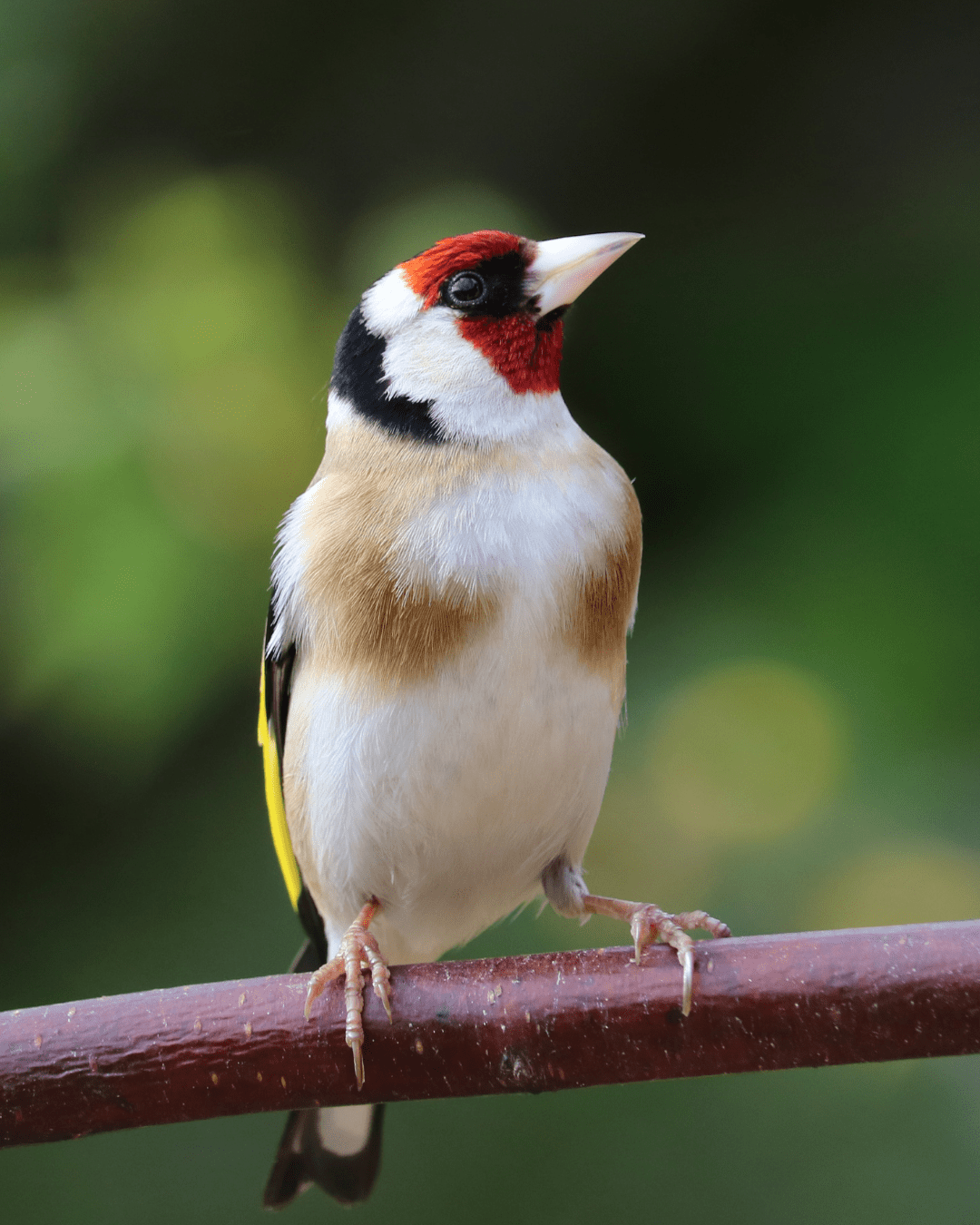

Why does a goldfinch have a red face

Goldfinches are my favourite birds, and I love their red masks. Their colouring is caused by carotenoids (pigments found in the food they eat), and a male’s mask is a deeper shade of red, while a female’s will have a more orange tone. If a female has a parasitic infection, she is less able to process carotenoids, meaning the shade of red on her face will be more orange. I had no idea that a goldfinch’s mask was such a strong indicator of her health!

Spider ballooning

Many smaller species of British spider, including the money spider, can travel on air currents for hundreds of miles and at altitudes of up to 10,000 feet. They stand on a high vantage point, such as a fence post or washing line, and lift their abdomens to release fine silk threads into the air, which carry them to where they need to go. They use their ballooning skills to escape predators (although one in every 17 invertebrates caught mid-air is a spider, so this tactic might backfire), leave an overpopulated area, disperse (as spiderlings), or find food. Fascinatingly, when there’s no breeze or thermals to carry the spider, they can use the Earth’s static magnetic field – favourable electric fields might actually trigger ballooning behaviour.

Tree-ly incredible

Did you know that a single oak tree can support over 2,300 species of animals and plants, making them the most ecologically valuable of all our British trees and one of the most wildlife-rich habitats in the UK? From caterpillars, squirrels, mice, bats, wasps, lichens, fungi, to (of course) birds, they are vital parts of our landscape. And what goes on beneath the soil in woodland areas can be even more interesting. Most trees communicate using their roots, but beech trees take it to the next level, sending sugars and minerals to weaker trees, warning neighbouring trees of danger (by releasing defensive chemicals if attacked by pests), and all the while prioritising their offspring over other beech trees.

Jamming bat echolocation

The garden tiger moth has learned to jam bat echolocation. It produces a rapid series of ultrasonic pulses using special structures called tymbals in the thorax. These sounds disrupt the bat’s ability to accurately detect and track the moth, effectively jamming its radar. The moth also startles the bat long enough for the moth to escape. Some bats, including the barbastelle bat, have adapted to reduce the volume of their echolocation calls, making it harder for the moth to hear them coming and giving them the element of surprise.

Hedgehog hair-dos

A hedgehog has 3,000–5,000 spines on his back, which he uses to defend himself against predators (and also to protect himself against the rain and as shock absorption). But did you know that those spines are actually made from keratin – the same substance that our hair is made from? That means that a hedgehog’s spines are continuously renewing themselves – if he loses a few in an encounter with a predator (or everyday wear and tear), he can quickly regrow them to keep himself safe.

Our gardens are full of surprises! From the amazing abilities of hedgehogs and frogs to the cleverness of squirrels and the teamwork of ants, there’s always something new to learn. Next time you head into the garden to fill up your bird feeder, you might want to try and guess the age of a ladybird, or try to woo a blackbird.